The History Of The Xhosa In The Central Karoo

Little has been written about the first Xhosas to venture into the Great Karoo. We have, however, discovered that several groups lived along the Gamka River from 1795 to 1799. The movement of small groups into Karoo during the late 18th century appears to have been caused by a century of frontier wars in the Eastern Cape as well as the aftermath of The Mfecane or Great Cattle Killing of 1856.

Unrest along the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony dates back to 1705. Constant clashes between Xhosa clans and settlers over land, water and grazing eventually exploded into nine major wars over 100 years from 1777 to 1877. British troops were brought face to face with black warriors they acknowledged as among their most dangerous foes in Southern Africa.

In Search of Grazing and Peace

The wars, constant cattle rustling, retaliation, severe droughts and torrential rain each forced Xhosa groups to seek shelter in the Great Karoo. Many early explorers encountered these groups near fledgling Karoo towns. Thompson, for instance, mentions a location near present-day Victoria West, while others describe the central area as a temporary and dynamic zone where conflict is endemic.

One of the earliest Xhosa men who moved into the Karoo and led Colonial forces on many a chase was Nzwane, a brother of the frontier leader, Ndlambe. Nzwane, an experienced ivory trader who at times lived in the Gamka River area near the Nuweveld Mountains, was known by several names, such as Nozi or Zonie. Eventually he became known as Danster, and it is possible that Dansterfontein, now part of the Karoo National Park, was his regular haunt. Danster in time became a formidable leader. Many commandos were raised against him. He was once arrested and deported, but escaped to return and continue his reign of terror in the hinterland.

When Danster first arrived in the Colony, he found it difficult to support himself, so he took a variety of jobs with Karoo farmers. While in the service of Roggeveld veldwachtmeester Floris Visser, a man with whom he had frequent and angry clashes, Danster learned to speak Dutch.

Powerful Men of the Nuweveld

Kallaway writes that Danster freely roamed the Karoo, moving as far south as Cape Town while acquiring guns and cattle on the way. By the time he moved into the Gamka River area, Danster had gathered a large swarm of followers. Some remained behind when he left for the Gariep (Orange River) area.

In 1799 another Xhosa, known as Thole, led a group into the Nuweveld area and for a short while lived on the banks of the Gamka River, south of present-day Beaufort West and north of Leeu Gamka. Thole and his followers eventually moved north to join Danster and other tribes gathering at the Gariep. The Orange River, with its many little islands and wooded banks, provided refuge for runaway slaves, dissidents, deserters, criminals, arms and liquor smugglers and outlaws. By 1800, Danster had gathered a large force there and was trying to control the ivory and cattle trade routes.

In 1806, cattle traders Hendrik and Jacob Organde settled with their followers in the Nuweveld area at the source of the Gamka River. When Danster swung back through the Karoo on a recruiting drive, after his following at the Orange River had diminished, he managed to charm Hendrik into accompanying him to the Gariep. Shortly after Hendrik and 30 of his men were killed in a skirmish.

Two years later, in 1808, Field Cornet De Beer, who was responsible for the Nuweveld area, reported 400 Xhosas in the Gamka area. He assembled a commando to move them off. Most proceeded to the Orange River, but some stayed in the Gamka and Nuweveld areas despite the increasing pressure from farmers and government officials. These people formed the core of black inhabitants living at the fledgling village of Beaufort West 10 years later.

Early in 1811, tensions began to build up towards the Fourth Frontier War in the Eastern Cape, causing yet another Xhosa movement into the hinterland. Elizabeth Anderson mentions a considerable number being given permission to move through the Colony in February, 1811, to settle along the Orange River.

Angry Nuweveld farmers, fearing their cattle would be stolen, demanded a commando be raised against them. The commando apparently did assemble, and the group moved peacefully through the Nuweveld area with farmers carefully watching grazing and water supplies to ensure passing herdsmen did not use too much of either.

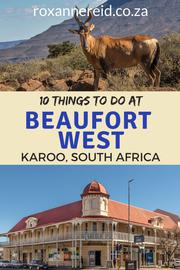

When Beaufort West was established at the request of Lord Charles Somerset in 1818, Black people in the im/mediate vicinity moved closer and set up dwellings in and around the town. Black and Coloured people, who were mostly descended from the Griekwas and Khoi Khoi, lived in among the White community in Bird and New streets and in the "Bodorp" for almost 60 years before a township was established, says Wynand Viviers.

The Great Cattle Killing

Xhosa groups streamed into the Karoo after The Great Cattle Killing of 1856. Continual warfare, stock losses and social upheaval, coupled to their herds being decimated by a lung disease, gradually weakened the Xhosa and caused them to turn to religion for guidance. They were captivated by the prophecies of a 14-year-old girl from the Gxarha River area north of the Kei River. Nongquwuse called on the nation to kill their cattle and burn their crops. If they did this, she said, their ancestors would rise, drive the British into the sea and return all their sacrificed cattle. The Xhosa were under such social and political pressure that they heeded her plea. Crops were destroyed and 400 000 head of cattle were killed. As a result 40 000 people died of starvation. The Xhosa wandered into the Karoo in search of work.

Sophie Grey, wife of Bishop Robert Grey of Cape Town described these Xhosa as little more than emaciated skeletons staggering into villages. Many of these men helped build some of the beautiful stone kraals that became a feature of the Karoo.

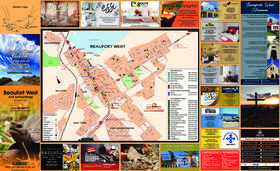

The small town of Beaufort West grew steadily, and within 60 years the city fathers felt it necessary to create a special zone for its non-White community. Again, the Gamka River area played central role.

A Township Is Established

In 1879, Beaufort West's town engineer, Avon Bruce-Brand, a former bodyguard of Queen Victoria and the man responsible for the building of the Springfontein Dam north of the town 10 years earlier, was asked to identify a suitable area for a Black location. He chose the southern side of the village and the western bank of the Gamka River. In little over a century, this area was to become Kwa-Mandlenkosi township.

Bruce-Brand tabled a proposal for the location at a council meeting on December 1, 1879. This was accepted on January 16, 1880, and he was instructed to divide the area into stands. People who could afford to pay a municipal tax of 2/6 d a month were allowed to build their own houses on these stands. Jonas Masimona was appointed supervisor of this first location on December 14, 1880. A kaia, or small dwelling of raw stone, was erected for him and he was given a salary of £3/10/- a month. Jonas held this position until August 21, 1883, when he was succeeded by F Potgieter.

By April, 1900, 466 adults and 514 children lived in the township, which for many years was home to both Black and Coloured people. Rustdene, Newtown and other Coloured townships eventually grew out of this one.

Expansion started gradually after 1925 when the government proclaimed the old location a Bantu area. Most residents at the time were Coloured. Expansion into Rustdene began in 1942 with the erection of 385 houses and continued well into the 1960s. The Black township, which mushroomed along the banks of the Gamka, was for years referred to as "The Location". It had a colourful collection of mud, stone, iron and hessian-covered huts. Because the hessian huts looked as if they were covered with sacking the area became known as Sakkiesbaai.

Shades of Light and Darkness

Over the years many representations were made to the local authorities about the improvement of conditions in the township. Eventually, the community felt its demands were being heard and they then changed the name from "The Location" to "Sidesaviwa", which means "at last we have been heard."

The township retained this name until clouds of conflict throughout South Africa gave rise to The Comrades, or freedom fighters. A youth leader, the 24-year-old Mandlenkosi "Tsaka" Kratchi, a promising young boxer, was shot and killed in a police raid on January 22, 1985. His death so shook the community that they opted to change the township's name to Kwa-Mandlenkosi (the place of Mandlenkosi) to honour his memory. In time, the main road and high school were also named in memory of this young comrade.

Mandlenkosi, fondly called "Tsaka" by his friends, was again honoured in September, 2001, when two trees were planted to commemorate him during Arbour Week. One is at the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, from where he was buried, and the other at his parents' home.

Books to read

- Elizabeth Anderson, MA thesis, A History of the Xhosa of the Northern Cape 1795 - 1879.

- Peter Kallaway, in his article Danster and the Xhosa of the Gariep traces some of this man's escapades in the central area.

- Wynand Viviers in Hooyvlakte, the Story of Beaufort West from 1818 to 1968.